In the 1926 short story “Pickman’s Model,” the narrator’s sanity has been frayed by a brush with things beyond everyday comprehension, with beings eldritch and architectures cyclopean. “You needn’t think I’m crazy,” he begins, which means you-know-what. The author of the Boston-set “Pickman’s Model” is an avowed Anglophile antiquarian with yearnings for the clean Yankee past, and he works in references to “peaked roof-lines” of the “pre-gambrel period,” as well as scornful references to the verminous lesser races that have since overrun the ancient precincts where he lays his tale. (“I’ll guarantee to lead you to thirty or forty alleys north of Prince Street that aren’t suspected by ten living beings outside of the foreigners that swarm them. And what do those Dagoes know of their meaning?”) “Pickman’s Model,” you might say, is a fairly representative H.P. Lovecraft story.

There are certain things that the admirer of Lovecraft must reckon with as a toll for entrance to his universe, much as admirers of Louis-Ferdinand Céline–phantasmagoric chronicler, in punchy street argot, of Europe’s suicide in two world wars–must reckon with the fact that, before and during the second, Céline inconveniently published two viciously anti-Semitic screeds, L’École des cadavres and Les Beaux Draps. The Jewish-American literary scholar and teacher Milton Hindus attempted to reconcile his admiration for Céline’s literary accomplishment with his Jewish conscience in a study called The Crippled Giant—and the same moniker might fit Lovecraft, whose long shadow will not recede from the popular imagination.

Lovecraft’s clubfoot, as it were, is the doctrine of white, Anglo-Saxon supremacy that flavors much of his prose. (See Glenn Kenny’s exegesis of Lovecraft’s “The Horror at Red Hook,” which appeared earlier this week). Those seeking to rehabilitate Lovecraft from his Horror at The Other can always quote him on the Republican party—“a frightened, greedy, nostalgic huddle of tradesmen and lucky idlers who shut their eyes to history and science, steel their emotions against decent human sympathy”—although this only goes so far, for before the Third Reich carried out Céline’s wildest hallucinatory visions with scientific precision, eugenics was very much a plank in the Progressive platform. Just ask everybody’s favorite Fabian Socialist, George Bernard Shaw!

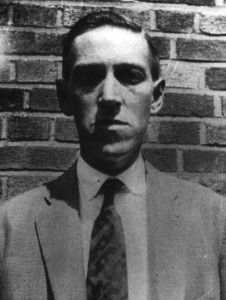

Through the years everyone has had a go at H.P., from Bunny Wilson (“The only horror is the horror of bad taste and bad art”) to Luc Sante. So much about the man invites mockery, not least his appearance. He had a head shaped like a gravedigger’s spade, bat ears, and tight, prissy mouth. Lovecraft made this physiognomy noble in the world he invented in his stories, where a “long thick lip” or “drooping of [a] heavy nether lip” is a sure sign of degeneration if not the dreaded miscegenation. He was, at the same time, a race-mixer himself, his only marginally successful adult relationship having been with one Sonia Greene, a woman of Eastern European Jewish stock to whom he was married for two years, during which time she supported her aristocrat-in-his-own-mind husband by working as a milliner.

Through the years everyone has had a go at H.P., from Bunny Wilson (“The only horror is the horror of bad taste and bad art”) to Luc Sante. So much about the man invites mockery, not least his appearance. He had a head shaped like a gravedigger’s spade, bat ears, and tight, prissy mouth. Lovecraft made this physiognomy noble in the world he invented in his stories, where a “long thick lip” or “drooping of [a] heavy nether lip” is a sure sign of degeneration if not the dreaded miscegenation. He was, at the same time, a race-mixer himself, his only marginally successful adult relationship having been with one Sonia Greene, a woman of Eastern European Jewish stock to whom he was married for two years, during which time she supported her aristocrat-in-his-own-mind husband by working as a milliner.

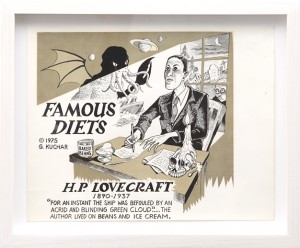

Greene would later describe Lovecraft as “an adequately excellent lover,” a phrase that has given me almost as many belly-laughs as this list of starchy, Anglo-Saxon names that Lovecraft gave to the faculty at Miskatonic University, a creation of his fiction and his “safety” after failing to attend hometown Brown University. Tales of “Wingate Peaslee” and company, however, didn’t pay the bills. In penury and suffering daily agony from cancer of the small intestine, which cannot have been helped by a vile poverty-imposed diet of tinned meat, Lovecraft died a thoroughly unimportant man in 1937, in the city of his birth, Providence, Rhode Island.

Lovecraft’s life story and his crippling neuroses are wrung for all their farcical worth in a three-page biographical comic that the late George Kuchar drew for the third issue of Bill Griffith and Art Spiegelman’s comic anthology Arcade in 1975. (“I don’t mind you making love with your clothes on, Howard,” Kuchar’s Sonia says, “but could you at least take your gloves off?”) And now, some seventy years later, the apocalyptic visions that appeared to penniless Lovecraft in light-headed rhapsodies have spawned a pop cultural empire of incalculable worth, yet too late to do their creator any good. It’s kind of funny, but really not very funny at all. A lot of things having to do with Howard Phillips Lovecraft’s life are like that.

How do we account for the tenacious grip that this outwardly ridiculous figure holds on the imagination? Let’s return to “Pickman’s Model.” In it, our harried narrator relates his visit to the secret studio of Pickman, a painter whose penchant for macabre subject matter has made something of a scandal in Boston, making him a reject of the Art Club, Museum of Fine Arts, and the Newbury St. galleries. Pickman’s studio is nestled far away from all of this, in Boston’s ancient North End, where the architect of the Salem witch trials, Cotton Mather, lies in Copp’s Hill Burying Ground. In Pickman’s studio, the narrator encounters canvases whose anti-human subject matter and photorealistic rendering far exceed that of any of the artist’s publicly displayed works, canvases in which “the awfulness, the blasphemous horror, and the unbelievable loathsomeness and moral foetor came from simple touches quite beyond the power of words to classify.” Earlier, our narrator opines:

How do we account for the tenacious grip that this outwardly ridiculous figure holds on the imagination? Let’s return to “Pickman’s Model.” In it, our harried narrator relates his visit to the secret studio of Pickman, a painter whose penchant for macabre subject matter has made something of a scandal in Boston, making him a reject of the Art Club, Museum of Fine Arts, and the Newbury St. galleries. Pickman’s studio is nestled far away from all of this, in Boston’s ancient North End, where the architect of the Salem witch trials, Cotton Mather, lies in Copp’s Hill Burying Ground. In Pickman’s studio, the narrator encounters canvases whose anti-human subject matter and photorealistic rendering far exceed that of any of the artist’s publicly displayed works, canvases in which “the awfulness, the blasphemous horror, and the unbelievable loathsomeness and moral foetor came from simple touches quite beyond the power of words to classify.” Earlier, our narrator opines:

Any magazine cover hack can splash paint around wildly and call it a nightmare or a Witches’ Sabbath or a portrait of the devil, but only a great painter can make such a thing really scare or ring true. That’s because only a real artist knows the actual anatomy of the terrible or the physiology of fear—the exact sort of lines and proportions that connect up with latent instincts of hereditary memories of fright, and the proper colour contrasts and lighting effects to stir the dormant sense of strangeness… Don’t ask me what it is they see. You know, in ordinary art, there’s all the difference in the world between the vital, breathing things drawn from Nature or models and the artificial truck that commercial small fry reel off in a bare studio by rule. Well, I should say that the really weird artist has a kind of vision which makes models, or summons up what amounts to actual scenes from the spectral world he lives in.

In Pickman’s canvases, our narrator finds the “anatomy of the terrible” and the “physiology of fear” in spades. Pickman continues the tour, leading the way into an earthen cellar dominated by a great well blocked up with a “heavy disc of wood.” The habitual Lovecraft reader knows straightaways what this is, for Lovecraft’s universe abounds in portals to other worlds, worlds populated by malevolent beings who clamber against the barred gates to ours. Startled by the unholy cacophony sent up by something beating against the well-cover, our narrator absently snatches a piece of paper attached to one of the incomplete paintings. This, when examined, betrays the secret of his friend’s art: “What it showed was simply the monstrous being he was painting on that awful canvas… It was the model he was using… it was a photograph from life.”

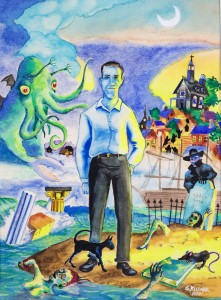

Pickman is H.P. Lovecraft’s self-portrait. “I do what I do so well,” he is telling us, “Because I am working from life.” I suspect that this utter conviction is the source of his reverberating power—the way that, while hearkening to a collective memory of atavistic terror, he seems to write with both feet planted and toes squelching in primordial ooze. “I always had the feeling that what he was talking about was real,” Kuchar says, bluntly, in Jennifer M. Kroot’s documentary portrait of the Underground filmmaking, It Came from Kuchar.

Pickman is H.P. Lovecraft’s self-portrait. “I do what I do so well,” he is telling us, “Because I am working from life.” I suspect that this utter conviction is the source of his reverberating power—the way that, while hearkening to a collective memory of atavistic terror, he seems to write with both feet planted and toes squelching in primordial ooze. “I always had the feeling that what he was talking about was real,” Kuchar says, bluntly, in Jennifer M. Kroot’s documentary portrait of the Underground filmmaking, It Came from Kuchar.

To find figures who made as much of a material flop in life as Lovecraft did and went on to have such posthumous impact, you’d have to go back to Van Gogh, Marx, or Christ. Neil Gaiman’s introduction to my Del-Rey edition of the Lovecraft collection Dreams of Terror and Death puts it quite succinctly: “Lovecraft’s influenced people as diverse as Stephen King and Colin Wilson, Umberto Eco and John Carpenter. He’s all over the landscape… Lovecraft is a resonating wave. He’s rock n’ roll.”

And yet, Lovecraft never seems to ace his screen test. He has 123 writer credits at IMDb. The earliest is nearly 30 years after his death (Roger Corman’s 1963 The Haunted Palace), while the vast majority are little-seen short films and various homemade whatzits of the last decade or so. I’ve heard positive things about Robert Cappelletto’s Pickman’s Muse and Tom Gliserman’s The Thing on the Doorstep, but haven’t watched either and therefore cannot speak for them. It’s altogether too much bother to riffle through a cottage industry of “adaptations” that essentially amount to Lovecraft cosplay for circulation among Cthulu cultists.

Of Stuart Gordon’s farcical 1985 Re-Animator, the best-known adaptation, I retain a faint, fond memory of Jeffrey Combs’ performance as Herbert West. If we widen our search to include works “inspired by” Lovecraft, I endorse Lucio Fulci’s films with scriptwriter Dardano Sachetti, City of the Living Dead, The Beyond, and The House by the Cemetery. The last images of The Beyond—Catriona MacColl and David Warbeck looking out across the eternal dusk of an ashen “Sea of Darkness” with marble-blank eyes—achieve a particular majesty, almost becalming in their total desolation. But greater talents still have stumbled into the “inspiration” domain. Paul Schrader’s 1994 HBO movie Witch Hunt, starring Dennis Hopper as a private investigator called Harry Phillip Lovecraft, is one of the worst things ever made by a major director. (Come to think of it, a couple of the others are also by Schrader.)

Of Stuart Gordon’s farcical 1985 Re-Animator, the best-known adaptation, I retain a faint, fond memory of Jeffrey Combs’ performance as Herbert West. If we widen our search to include works “inspired by” Lovecraft, I endorse Lucio Fulci’s films with scriptwriter Dardano Sachetti, City of the Living Dead, The Beyond, and The House by the Cemetery. The last images of The Beyond—Catriona MacColl and David Warbeck looking out across the eternal dusk of an ashen “Sea of Darkness” with marble-blank eyes—achieve a particular majesty, almost becalming in their total desolation. But greater talents still have stumbled into the “inspiration” domain. Paul Schrader’s 1994 HBO movie Witch Hunt, starring Dennis Hopper as a private investigator called Harry Phillip Lovecraft, is one of the worst things ever made by a major director. (Come to think of it, a couple of the others are also by Schrader.)

No Lovecraft acolyte in Hollywood today has more clout than Guillermo del Toro, and adapting the lean master’s 1931 novella At the Mountains of Madness has been his long-cherished dream project. A screenplay by del Toro and Matthew Robbins was very nearly greenlit by Universal in 2011—budgeted at $150 million, to star Tom Cruise and be shot in 3D—but then along came Ridley Scott’s Prometheus which, like Mountains, used the plot device of ancient astronauts, and so del Toro fell back on Pacific Rim instead. Today scarcely a dozen of the millions of people who saw Prometheus can remember any single detail of its plot, which means Del Toro can hope anew to make Mountains—though after Pacific Rim I don’t expect more than a molehill from the resulting movie. Del Toro is by universal decree “the nicest guy in Hollywood,” and his fanboy references are impeccably in order, but he’s never convinced me as a nut-and-bolts filmmaker. Who, then, to make the great American Lovecraft adaptation?

It happens to already exist. Although the name “H.P. Lovecraft” is nowhere to found on it, it’s a short leap from “At the Mountains of Madness” to John Carpenter’s In the Mouth of Madness. Tom Allen, the Jesuit monk and erstwhile Village Voice film critic who was one of Carpenter’s earliest and most astute supporters (and also the subject of a recent effusion by yours truly), attempted to define “the Carpenter touch” in 1980: “It is entertaining, intelligent, frequently derivative, and quintessentially American in its creative comfortableness with genre forms.”

Most of the above holds true of In the Mouth of Madness, though it is maybe Carpenter’s most uncomfortable genre production. As Carpenter has told numerous interviewers over the years, he read his first two Lovecraft stories as a boy—“The Dunwich Horror” and “The Rats in the Wall”—in a Modern Library Giant Edition, and he never shook the tentacles loose. He tried to pitch Lovecraft’s “The Colour Out of Space” as a NBC miniseries. His 1980 The Fog features a brief mention of “Arkham Reef,” a reference to a city of Lovecraft’s invention which would lend its name to a publishing company founded by August Derleth and Donald Wandrei, who released Lovecraft’s collected works after his death and continued to spread his gospel of threatening Armageddon. “Frank Armitage” is both the name of Keith David’s character in 1988′s They Live and that film’s credited screenwriter; the nom de plume comes from Lovecraft’s “The Dunwich Horror,” and the screenplay is in fact by Carpenter. “Lovecraft wrote about the hidden world,” Carpenter would tell an interviewer, “the world underneath. His stories were about gods who are repressed, who were once on Earth and are now coming back. The world underneath has a great deal to do with They Live.”

Most of the above holds true of In the Mouth of Madness, though it is maybe Carpenter’s most uncomfortable genre production. As Carpenter has told numerous interviewers over the years, he read his first two Lovecraft stories as a boy—“The Dunwich Horror” and “The Rats in the Wall”—in a Modern Library Giant Edition, and he never shook the tentacles loose. He tried to pitch Lovecraft’s “The Colour Out of Space” as a NBC miniseries. His 1980 The Fog features a brief mention of “Arkham Reef,” a reference to a city of Lovecraft’s invention which would lend its name to a publishing company founded by August Derleth and Donald Wandrei, who released Lovecraft’s collected works after his death and continued to spread his gospel of threatening Armageddon. “Frank Armitage” is both the name of Keith David’s character in 1988′s They Live and that film’s credited screenwriter; the nom de plume comes from Lovecraft’s “The Dunwich Horror,” and the screenplay is in fact by Carpenter. “Lovecraft wrote about the hidden world,” Carpenter would tell an interviewer, “the world underneath. His stories were about gods who are repressed, who were once on Earth and are now coming back. The world underneath has a great deal to do with They Live.”

As it does, for that matter, with 1986’s Big Trouble in Little China, 1987’s Prince of Darkness, and In the Mouth of Madness. The capstone of an unofficial “Apocalypse Trilogy” including Prince of Darkness and 1982’s The Thing, In the Mouth of Madness was released in February 1995. In standard Lovecraftian fashion, the story begins in an asylum (“I’m not insane, do you hear me?…”) Carpenter loves to prowl institutional corridors with his camera, and did so to great effect in his latest-and-hopefully-not-last directorial outing, 2010’s better-then-you-heard The Ward. The inmate here is John Trent (Sam Neill), and how he came to misplace his mind is our story. The unraveling began when Trent, once a best-in-the-business insurance fraud investigator, was hired to go after a bestselling novelist named “Sutter Cane” who went missing before delivering his next novel, the eponymous In the Mouth of Madness. Cane’s name and phenomenal success suggest Stephen King, but the titles of his novels (The Hobb’s End Horror, The Haunter Out of Time, The Breathing Tunnel, The Whisperer of the Dark) and the be-tentacled beings decorating Cane paperbacks are pure Lovecraft.

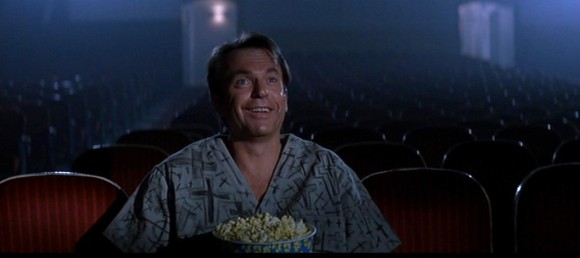

Deciphering a clue cobbled from the composite cover art of Cane’s books, Trent theorizes that the author has retreated to an off-the-map hamlet in rural New Hampshire—and is convinced that the entire disappearance is a stunt to drum up publicity. With an attaché from the publisher in tow (Julie Carmen), Trent dutifully heads for Hobb’s End, where they check in at, naturally, The Pickman Hotel. From here strange things start happening, and they do not stop happening until a final act that has Trent wandering out of the depopulated madhouse and plunking down in a movie theater where, wearing an idiot grin, Sam Neill proceeds to guffaw at Sam Neill’s performance in the adaptation of Cane’s In the Mouth of Madness—the very movie we’ve been incredulously watching.

Deciphering a clue cobbled from the composite cover art of Cane’s books, Trent theorizes that the author has retreated to an off-the-map hamlet in rural New Hampshire—and is convinced that the entire disappearance is a stunt to drum up publicity. With an attaché from the publisher in tow (Julie Carmen), Trent dutifully heads for Hobb’s End, where they check in at, naturally, The Pickman Hotel. From here strange things start happening, and they do not stop happening until a final act that has Trent wandering out of the depopulated madhouse and plunking down in a movie theater where, wearing an idiot grin, Sam Neill proceeds to guffaw at Sam Neill’s performance in the adaptation of Cane’s In the Mouth of Madness—the very movie we’ve been incredulously watching.

A few word about Neill’s smugly skeptical Trent. The performance, in every individual part and in overall effect, is unnatural, anti-intuitive, needlessly busy, and just plain strange. Neill exhales with a theatrical hiss when smoking, gives the twin gables of his eyebrows a real workout, flashes a charmless, rabbity smile at inappropriate moments, and allows his accent to wander between Christchurch and Philadelphia without ever sounding at home in either. At the same time, the amount of fussy detail work that goes into this strangeness is remarkable; let’s not forget that Neill was mentored by no less a personage that James Mason. This isn’t bad acting, precisely, it’s wrong acting—in the same sense that Charlton Heston is wrong as a bluff publishing house head, and Toronto is wrong in the role of New York City.

In the Mouth of Madness is set in New England and NYC, but was shot around Ontario and Toronto, a city that David Cronenberg’s entire career has been committed to proving can never look like anything other than Toronto. In fact, to the eyes of someone from the United States, it doesn’t really photograph as a city at all—it’s too clean, too fresh, almost like a soundstage. Madness returns repeatedly to a “filthy alleyway” that looks remarkably like the exhibit representing “urban decay” in the Creation Museum in Petersburg, Kentucky. This obvious artifice is all the more curious when one considers that In the Mouth of Madness was made not so very long after Prince of Darkness and They Live, two movies that make excellent use of locations in seedy Downtown Los Angeles.

Carpenter’s decision to shoot in Canada is justified by the unveiling of Hobb’s Ends’ Black Church—in fact the lonesome, glowering Cathedral of the Transfiguration, a Slovak Byzantine Rite Roman Catholic church some ways outside of Toronto, in Markham. When Trent finally catches up with Cane, played by Jürgen Prochnow, the author has taken up residence in this fortress of solitude. His study is a room whose walls are swirled in gore, like Beatrice Dalle’s finger-painting job in Trouble Every Day, and which is dominated by a massive door whose slimy boards pulse and writhe as though tormented and alive. This is Cane’s passage to communicate with his otherworldly inspirations, his Pickman’s well. “For years I thought I was making all this up,” Cane says, “but they were telling me what to write.” Like Pickman or Lovecraft, Cane’s line is nonfiction.

Carpenter’s decision to shoot in Canada is justified by the unveiling of Hobb’s Ends’ Black Church—in fact the lonesome, glowering Cathedral of the Transfiguration, a Slovak Byzantine Rite Roman Catholic church some ways outside of Toronto, in Markham. When Trent finally catches up with Cane, played by Jürgen Prochnow, the author has taken up residence in this fortress of solitude. His study is a room whose walls are swirled in gore, like Beatrice Dalle’s finger-painting job in Trouble Every Day, and which is dominated by a massive door whose slimy boards pulse and writhe as though tormented and alive. This is Cane’s passage to communicate with his otherworldly inspirations, his Pickman’s well. “For years I thought I was making all this up,” Cane says, “but they were telling me what to write.” Like Pickman or Lovecraft, Cane’s line is nonfiction.

By this point, we’ve already seen a paperboy (Hayden Christensen!) transform into a husk of an old man (who bears a passing resemblance to present-day Carpenter) wearing double-denim, a painting whose figures won’t stay in place, and other inexplicable, uncanny occurrences. Jonathan Rosenbaum was fairly on the button when observing that, with In the Mouth of Madness, “Carpenter seems to have entered David Lynch territory”—or is it Herk Harvey territory? In this atmosphere of the incredible, Neill’s performance suddenly assumes a degree of credibility. In fact, its overall wrongness seems to correct itself as the movie shakes off the fetters of realism entirely and begins to obey the nightmare logic of Cane’s world—Carpenter’s “world underneath.” In this respect, Madness is the perfect adaptation of Lovecraft’s prose. H.P. couldn’t write three lines of casual, quotidian conversation to save his life, but oh, could he ever produce reams of prose pictures detailing astral terrors or savage, deposed beast-Gods come to reclaim the world they left behind.

And there’s no doubt that it is their property. What one takes away from In the Mouth of Madness—so queer in realism, so lucid in dementia—is a feeling that normalcy is an anomaly waiting to be corrected, a temporary respite before mankind is dragged back to his natural state in the mire of terror and illogic. The film’s apparent defects are accordingly revealed to be its strengths, and its fidelity to Lovecraft’s worldview, purged of its more noxious elements, has never been bettered. In fact, I would go so far as to rank Madness among Carpenter’s highest accomplishments. You needn’t think I’m crazy… I’m not mad, do you hear me?

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Sight & Sound magazine and sundry other publications. He lives in Brooklyn, NY. Follow Nick on Twitter @NickPinkerton.

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Sight & Sound magazine and sundry other publications. He lives in Brooklyn, NY. Follow Nick on Twitter @NickPinkerton.